Tornados started in western Mississippi on March 24, eventually knocking out the power of more than 80,000 homes and businesses across Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee.

Another series of convective storms broke out on March 31 and continued through April 5, destroying areas in Tennessee and Indiana, claiming at least 37 lives and injuring over 200.

Both events at one point produced tornados that were assigned with an Enhanced Fujita (EF) rating of 4 out of a 0-5 scale by the National Weather Service.

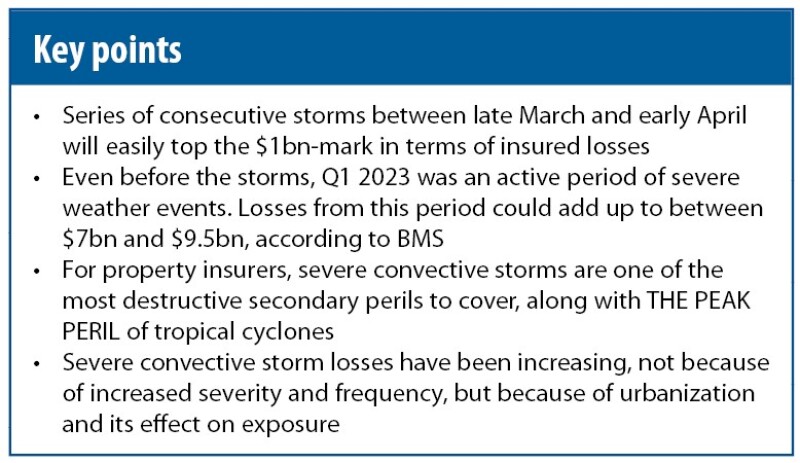

“It's very, very safe to assume that we're looking at least at a billion-dollar sequence of events” since late March, Gallagher Re chief science officer Steve Bowen told Inside P&C.

“It could be well above $1bn – potentially could get close to a multibillion-dollar event. But it's still too early to say definitively.”

In a report last week, BMS Group’s senior meteorologist Andrew Siffert estimated that the impact from March 31 events alone could be in the $3bn range.

The losses will fall on a property market which is already seeing surging rates and tightening terms amid a sharp withdrawal of capacity and rising reinsurance costs.

As previously reported, secondary perils such as tornados – which are challenging to model and price accurately – are also driving an increasing proportion of losses at property insurers.

Severe consecutive storms and their manifestations – hail, tornado and wind gust – typically impact small geographic areas. Such granularity makes it difficult for them to be picked up by catastrophe risk models, Siffert said.

Also, storm risks are complex. Hail, for example, can affect roofs in different ways according to the roof type, and therefore has a wider range of secondary risk characteristics that can drive losses.

The National Weather Service counted 618 storm reports on March 31, making it the most active day this year to date, substantially above the list’s second-place 318 reports for January 12. The figure combines reports of tornados, wind damage and large hail – all manifestations of convective storms.

The day was a historic one for tornado counts alone, with 104 touchdowns. According to Bowen, this is the highest number of tornados ever recorded in a single day during the month of March.

Even before the March events, tornado activity was double the 30-year average. Preliminary data from the NWS’s Storm Prediction Center suggests the occurrence of between 144 and 222 tornados during the first two months of the year, well above the 30-year average of 76.

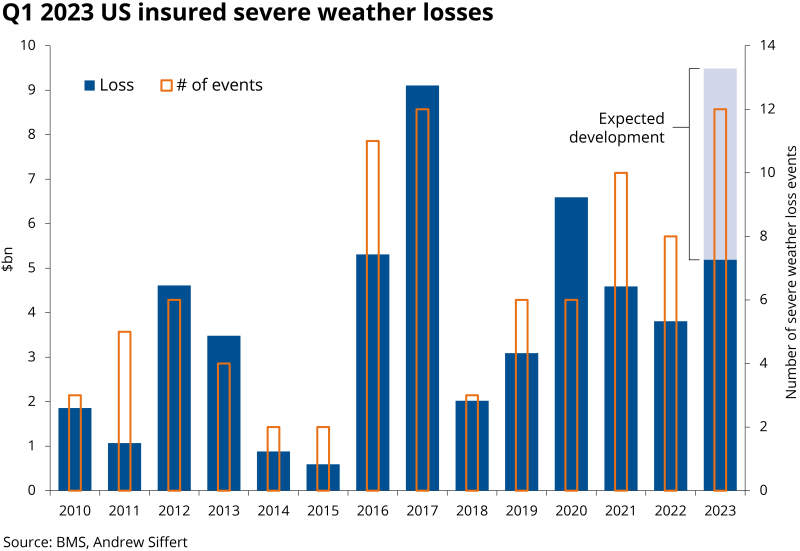

Siffert estimated that the industry was already close to a $6bn loss before the end of March. The events at the end of that month pushed aggregate losses up to total $7bn-$9.5bn for the entirety of Q1 2023, he said, adding that the quarter seems “to be or at close to a modern-day record” on a CPI-adjusted basis.

But the BMS executive said the dice seem “loaded for a higher occurrence of severe weather” during this period. “From the climate forces I looked at, the ingredients are there for a continued act of severe weather season through April and May.”

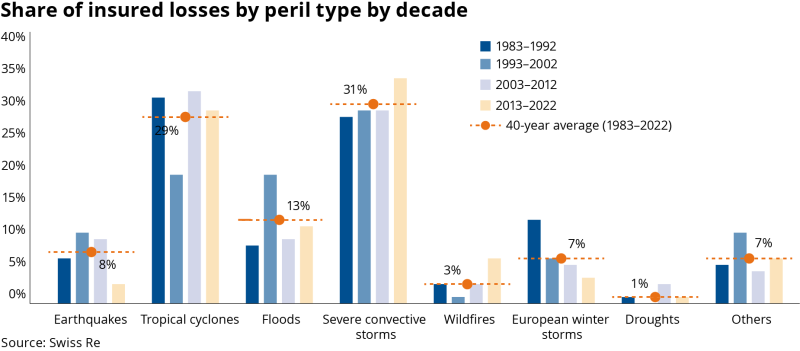

For property insurers, severe convective storms are one of the most destructive secondary perils to cover, along with tropical cyclones. In 2022, they resulted in $39bn of insured losses globally, placing them second on the list of most costly perils along with tropical cyclones ($59bn) and drought ($15bn), according to Gallagher Re.

Several carrier sources have pointed to a trend where underwriters are taking a conservative stance when it comes to offering storm coverage in the form of restrictive language, higher pricing for areas with loss history or imposing percentage deductibles, which are typically associated with hurricanes.

“I think this gets back into whether we should be calling this a secondary peril anymore because [of] the losses aggregated together […] being hurricane levels of losses,” Bowen said.

“It's a very dominant peril. And frankly, it's affecting a lot of insurers and their quarterly earnings reports.”

No longer secondary?

Convective storms happen all over the world, but the US represents around 20%-30% of globally insured losses. While local media tend to focus on tornados as they are linked to fatalities, the primary loss driver for P&C insurers is hail, according to company experts and reports.

According to Swiss Re’s Sigma report, severe convective storms in North America alone cost $26bn in insured losses last year, which compares to the $50bn-$65bn insured loss estimate for Hurricane Ian. This was “well above” the inflation-adjusted average of the previous 10 years, it stated.

But looking forward, the reinsurer forecasts that severe convective storm losses will likely exceed $25bn annually in the coming years and reach $30bn by the end of the decade, which would be equivalent to around 7% of projected US property sector premiums.

Unlike hurricanes, the reason convective storms are getting more expensive for (re)insurers is not to do with increasing frequency or severity. In fact, meteorologists say there is no scientific data that suggests a significant uptick in storms hitting the US.

Tornado figures, for example, show that the US is in the midst of its longest EF-5 tornado drought since it started compiling relevant data in the 1950s. The latest had hit Oklahoma in May 2013, resulting in 24 fatalities and 200+ injuries.

Some studies have shown that the warming climate may be shifting the prime location of tornados to the southeast of the country. But overall, the number of tornados and occurrences of hail in the US has not changed much above an incremental increase, which Bowen attributed to better reporting technologies.

Rather, the real driver behind increasing convective storm costs is urbanization and its effect on loss exposure.

“This all goes back to how we're building, what we're building [as] the density of the population continues to expand. We're growing essentially the bullseye in terms of what can be impacted by these storms,” Bowen said.

“So regardless of whether or not there is a change in the number of events that are occurring, the fact that there is more potential for stuff to be damaged is automatically going to be leading to higher loss costs – and that's what we've seen.”

BMS’s Siffert noted that urbanization is expanding the boundaries of US cities. This pushes the population away from the city center and as a result, areas that storms used to hit as cornfields or soybean fields are now housing developments.

Moreover, building costs have risen faster than the general rate of inflation, which means reconstruction costs and claims are about to get even higher.